I’d like to take you on a virtual tour to share how our focus on grazing carries over to the land and livestock. When you’e buying bulls, you should know how the cattle are raised. In the simplest form, we’re trying to:

- work with nature to improve forage production,

- develop the right genetics so the cows fit the environment,

- reduce the cost of production, and

- increase the pounds of beef raised per acre.

I’m not saying everybody should do things the way I do. Every ranch and operation is different, but these principles are working for us.

To lower production costs, we're trying to match the nutritional need of the cow with available forage. We start calving in the middle of May. During the winter, the cows are dry and in the second trimester of pregnancy.

January is a tough time to calve cows, but we used to do it. The timing locked us into having the cows close to shelter, and we had to provide good quality hay until grass came on. With current management, we have more flexibility to graze.

When we feed hay, we try to improve some of the range as well as feed cows. We'll unroll hay on bare spots and let the cattle break the soil crust and trample some of plant matter into the ground, adding manure and urine. The combination of organic matter and hoof action contributes to recruiting plants into the problem areas.

Wind erosion is a big deal in our area. Farm fields can blow, losing precious topsoil. Bare ground in pastures can also blow, removing topsoil and leaving pedestals of grass. Managing to improve plant density and diversity is key to managing soil health and moisture.

I think March might be the most challenging month to calve. Snow, wind and mud are tough on calves and people.

April snow is a blessing—unless your trying to thaw out newborn calves. Our cool season grasses are greening up in April and we can have 30+ days of high-quality feed prior to calving in late May. With a 50-day calving season, peak lactation—peak nutritional demand—will be close to peak grass production. The first of June would probably be about perfect time to calve in our area in most years.

Blue grama grass is our "go to" grass in the region (and Colorado's state grass). It's a warm season grass that can withstand heavy grazing pressure and our semi-arid climate. But to graze year-around, or close to it, we need to extend our periods of green grass. Recruiting cool season plants back to the range is good for the cattle, the soil and the pocketbook.

Given a chance, western wheatgrass (a cool season native plant) populations increase fairly quickly, providing good early-season forage and a late-season boost. We also utilize former CRP acres dominated by smooth brome.

When we calve in late May and June, the cattle are in fairly large pastures. I check them twice a day. Heifers and cows need to be able to calve unassisted. I also find we get very few calves at night.

We develop the heifers the same way we run the cows. They don't all make it to being cows, but we let nature decide which ones fit the environment.

I provide mineral and salt as needed. I drag these feeders to new spots to help manage cattle distribution. It's also a way to trample cactus infestations.

Cheat grass is a bummer, but it makes good early season forage. And what we don't graze can make good litter if we can get in trampled onto the ground. Opportunities sometimes masquerade as problems.

Most years we have water in several playas, but the standing water is a missed opportunity for growing grass. As our pastures improve, infiltration rates get better, runoff and erosion decrease, and we better utilize the rain.

We use tire tanks with geo-thermal heat tubes to make four-season water facilities. We place the tanks in enclosures to facilitate watering different paddocks and to change cattle behavior. Cows will come in a few at a time and then walk back to the herd, instead of all coming in at once and loitering around the tank.

With sufficient water turnover, we don't chop much ice. Even at 0°F, the cows have been able to open up the water on their own.

With the enclosures around the water tanks, we'll see cattle come in a few at a time and go back out to the herd. After the heifer calves are long weaned, we turn them back in with the cows.

Some of our pastures are rugged. Cattle have to be able to travel. Over-fat cattle can't walk a mile or more uphill to water and still thrive. The white spots on the ground are ancient sea shells.

Since we moved calving in the late spring and early summer, we've found we have very few sick calves. At branding time, we do a vetinarian-recommended vaccination protocol.

To measure the effectiveness of our efforts to improve the range, we do monitoring—photo points (including drone imagery), clippings, and infiltration tests at a number of places around the ranch. Our friends at the NRCS have been both encouraging and a great help—can't thank them enough.

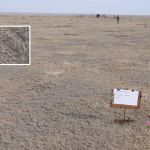

This is an example of a photo point that was taken in winter 2011. The inset is a second picture we take looking straight down at the same time to monitor plant density and plant litter. Through 2011, this pasture was managed in a conventional summer continuous graze system.

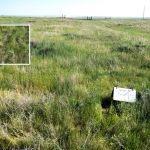

This is the same pasture as pictured in the previous slide after five years of managed rotational grazing (spring 2016). Not all of the plants are desirable, but the trend is moving in the right direction. I don't think there is any question which condition will be best for capturing and retaining rainfall.

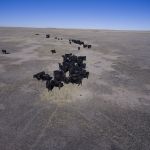

The drone has provided an interesting perspective to our photo points. We've been experimenting with altitudes and angles to find a useful balance.

We use a combination of permanent high-tensile and poly wire fence to break pastures down into smaller paddocks. During the peak growing season, we'd like to be in any given paddock less than a week. Commonly the word 'rest' is used in describing pasture rotations. I think 'recovery' might better a better term to describe the goal.

Bare ground is our enemy. To improve plant cover, we use cattle density and hoof action to break the hard crust on bare soil. Then we want to get the cattle to another pasture to give the plants a chance to recover and grow. In the best case, we want to trample some plant litter into that soil as a mulch. A reduction in bare ground is a key measure of progress.

It's been slow, but managed grazing can impact the populations of prickly pear. Plant litter fosters parasites that attack the pads.

Winter 2011—This pasture had been in a continuous summer graze use for many years. Note the erosion, lack of cool season plants (hard to see in a small picture) and cow patties not breaking down. The next picture is five years later.

Spring 2016—During the five years in-between pictures, we had both the driest and wettest years on record. Managed grazing helped nature shift plant composition and reduce bare ground. We've slowed erosion and capture more rainfall while we harvest the same or more AUMs as under the previous management. We also finish the year with a drought reserve.

Using portable facilities wherever the cattle are grazing, we A.I. all of our heifers and cows and then turn out a clean up bull for 60 days. We look at all of the EPDs for sires and make individual mating decisions. We're going to hold down the milk EPD and look to the $EN index to produce easy-keeping cattle. Between breeding and pasture rotations, our cattle are handled frequently. Fertility (bring in a calf every year) and docility are no-compromise traits.

Our philosophy is to manage for what we want, and not worry too much about the other plants. On part of the ranch, we schedule grazing to foster the health of fourwing saltbush. This native shrub is palatable to both livestock and wildlife, and provides good protein in the late fall and winter. Continuous grazing results in a decline in the health of many species of grasses, forbs and shrubs.

We ranch in a 12" average annual rainfall zone. Our ability to best utilize that meager precipitation is at the heart of the management strategy. To achieve that end, we need to be constantly improving soil health through plant diversity and cover.

We see wildlife as an indicator of ecosystem health. As pastures improve, we attract more wildlife. Weeds find opportunity where pastures are in poor condition. As the pastures improve, the weeds diminish.

The early part of the pasture improvement process was difficult. The initial abundance of red threeawn and sand dropseed was discouraging but we're seeing a better plant community with time.

On any given year, a pasture can only grow so much grass, but management can impact the trend and prepare for the 'dry one' that is always possible.

Instead of chasing weaning weights, fitting the cow to the environment and increasing pounds of beef sold per acre is better math. The net—income less expenses—determines profit. The largest single expense on most ranches is harvested feed.

The bulls are raised on pasture. This is a representative picture from October 2016. The bulls get some supplemental protein in the winter, but otherwise we keep them grazing. In February and March, we usually bring them to a small trap near the house to make them easier to show. While in this area, they will get hay.